n May of this year, China claimed a breakthrough in tapping an obscure fossil fuel resource: Researchers there managed to suck a steady flow of methane gas out of frozen mud on the seafloor. That same month, Japan did the same. And in the United States, researchers pulled a core of muddy, methane-soaked ice from the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

Read this article in ESPAÑOL or PORTUGUÉS.

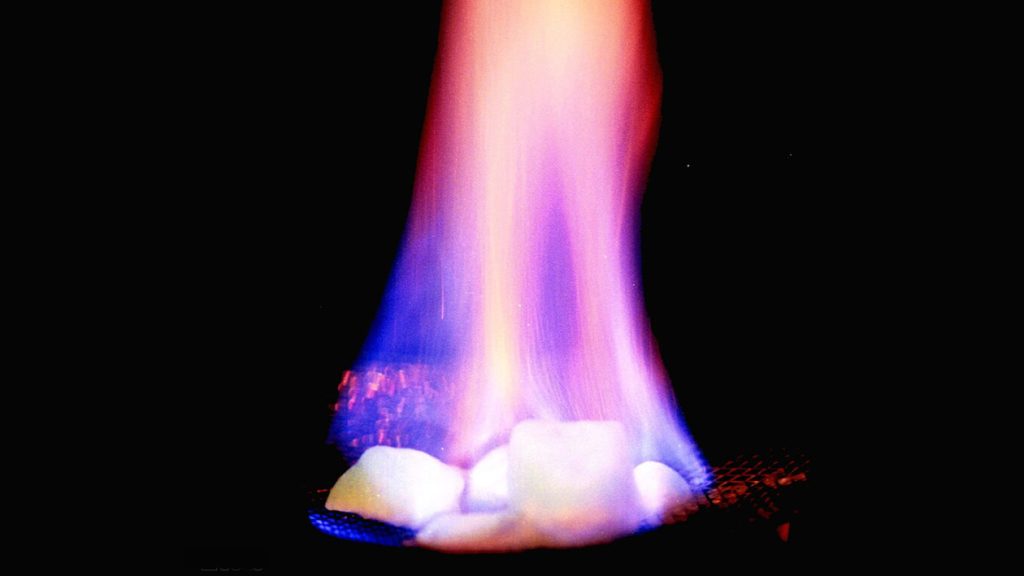

The idea of exploiting this quirky fuel source would have been considered madness a couple of decades ago — both wildly expensive and dangerous. Until recently, methane-soaked ice was considered explosively unstable. In the Gulf of Mexico, traditional oil rigs have been tiptoeing around these icy deposits for years, trying to avoid them.

“These deposits have been a pain in the neck for oil exploration,” says Scott Dallimore with the Geological Survey of Canada. Accidentally melting deposits overlying traditional oil and gas fields could cause drilling infrastructure to collapse, or pipes to clog up with ice. After the Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, for example, water and methane formed an icy plug that scuppered one attempt to halt the oil spill.

Now the tide has started to turn, as studies of the frozen gas have quelled some of the bigger fears. “We always used to think of these as explosive and dangerous — they’re not,” says Dallimore, who is involved with Canada’s explorations of these deposits. These reassuring findings, combined with rising energy demands, have spurred some countries — especially fossil fuel-poor nations like India and Japan — to think seriously about commercial extraction.

But there are still concerns about the wisdom of mining this unexplored corner of the fossil fuel landscape, including the possibility of triggering underwater landslides, unleashing tsunamis, disturbing ocean ecosystems, and — most important of all — more than doubling the planet’s natural gas supplies and the planet-warming emissions that go along with them. So is drilling for methane hydrates really a good idea?

For decades now, mankind has been chasing fossil fuels in smaller, weirder, and harder-to-get crevasses of the Earth. In the 1990s, the asphalt-like sludge of Alberta’s oil sands started to look like a viable resource; by 2003, thanks to changing technologies and economics, Canada’s standing in the international oil reserve tables rocketed to second place, behind Saudi Arabia. Then, around 2008, hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, became all the rage: Fossil fuel companies started injecting water, sand, and chemicals into shale rocks to split them apart and suck the natural gas out of the cracks. Both technologies, with their attendant environmental problems, have been grabbing headlines ever since.

Methane-soaked ice is the newest, strangest resource competing to be in the list of exploitable gas.